Delphi: Navel of the World

THE BEGINNING

Roman period omphalos at Delphi, covered by woollen netting (‘agrenon’). Source - Wiki - Yucatan

Legend has it that Zeus was determined to discover where the centre of the world lay. And so he sent out two eagles from each end of the cosmos. They met at Delphi which Zeus then declared was the omphalos (navel) of the world and which, over centuries, transformed itself into the leading oracular sanctuary of the Classical world.

The oracular sanctuary of Delphi lies on the steep slopes of Mount Parnassus offering spectacular views over the plain of Krisa some 600 metres below, with the ancient port of Kirra further in the distance. This meant that those pilgrims wishing to consult the Oracle had to either travel by sea to Kirra, and then ascend the slopes of Parnassus, or make the arduous journey from their home by land.

The site of Delphi began as a small Bronze Age (Mycenaean) settlement whose local cults were presided over by the legendary serpent Pytho before it was overthrown and slain by Apollo who had arrived from the north.

It was following Apollo’s arrival that Delphi slowly grew during the first millennium BCE, to become by late Archaic and Classical times (c. 600 – 300 BCE) the most powerful and influential oracle of the ancient world and one that could determine man’s good or bad fortune.

White-ground cup from Delphi. Apollo on a folding stool holding his lyre and a libation bowl. The crow opposite is a symbol of prophecy. Source - Wiki - Sharon Mollerus

THE SITE

The path through the sanctuary winds its way upwards and can be divided into three sections. The first of these sections entered by the pilgrim is the ‘Sacred Way’, consisting of a series of votive monuments set up by various city states (poleis) and often commemorating victories over rival cities that may have a similar monument nearby! On nearly all of these monuments were placed numerous commemorative statues (mainly in bronze), with most plundered during Roman times.

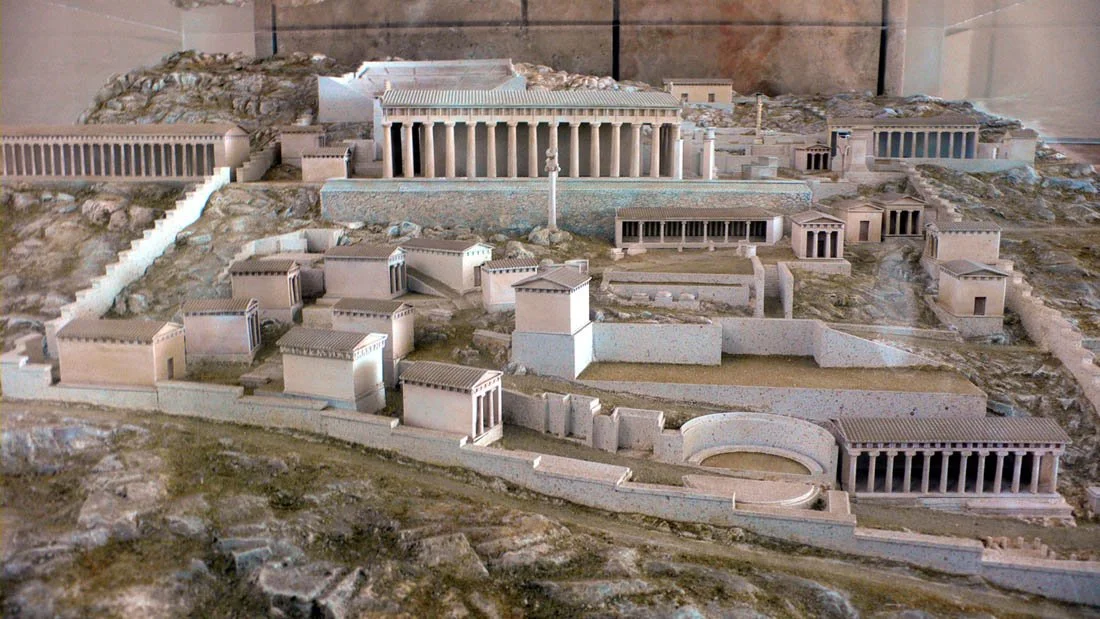

Model of Delphi in the Hellenistic period. The Sacred Way is entered from the lower right corner of the model. Note the stoas (porches) financed by Hellenistic kings on either side of the boundary wall.

Further along the Sacred Way are the Treasure Houses built by the various poleis to house those valuables dedicated in honour of the Oracle (often referred to as the ‘Pythia’). Of these, the most prominent is the Treasury of the Athenians, reconstructed in the early 20th century. From the third century BCE onwards many inscriptions, including those referring to the victors at the Pythian games (see below), were cut into the walls of this treasury. Most important, however, is an inscription of two hymns in honour of Apollo, sung at the Pythian festivals of 138 and 128 BCE. Uniquely they include instructions as to the musical notation for the hymns, shedding valuable light on the performance of Greek music in antiquity.

Treasury of the Athenians

The second section is the heart of the sanctuary, with the Pythia (usually a female from the local village) delivering her pronouncements from within the Temple of Apollo, which was built above a superbly constructed polygonal wall that forms the back wall of the Stoa (Porch) of the Athenians.

The Stoa of the Athenians below the Temple of Apollo

Temple of Apollo (rebuilt in fourth century BCE)

The third, and highest, section is dominated by the 4th century theatre which was an important structure in the Pythian games. Like the Olympic Games, they were held every four years and involved a mixture of athletic, equine and dramatic contests, with the winners receiving a wreath of laurel. While dramatic performances were held in the theatre, the athletic contests were held in the stadium further up the slope to the north-west of the sanctuary itself with the hippodrome (still buried) being located on the plain of Krisa.

Theatre overlooking the Temple of Apollo just below

View of The Stadium

Below and to the east of the sanctuary itself is the Precinct of Athena Pronaia (‘in front of the sanctuary’) with its several treasuries and two temples to Athena. Also in the precinct is the magnificent tholos (round building) which, despite its unclear function and ruined state, must rank as one of the most beautiful structures in ancient Greece.

Precinct of Athena Pronaia

THE CONSULTATION

Pilgrims made the arduous journey to Delphi to consult with the Oracle, and it is worth examining this consultation process more closely. Although we have a valuable description left by the Greek philosopher and historian Plutarch (himself a priest of Apollo at Delphi for several years), is not fully clear as to the entire process. The Pythia was certainly not ‘open for business’ every day, being closed for three winter months (when she travelled to the ‘land of Hyperboreans’). For the remaining nine months, the Oracle was open on the seventh day of each month, provided things were auspicious.

Pythia, priests, and enquirer first purified themselves at the nearby Castalian Spring before proceeding to temple where the enquirer offered an expensive sacred cake as a ‘consultation fee’ outside, and then proceeded inside the temple itself where a further sacrifice of a sheep or goat was made. However, only the Pythia was permitted inside the inner sanctum (adyton) where she was seated on a tripod and received the enquirer’s question from the temple priests who then ‘translated’ her incoherent utterings, said to be brought on by the burning or perhaps chewing of laurel leaves and inhalation of gases formed in a cave below the temple, into a coherent reply. The priests would then deliver her reply either directly to the enquirer or (if on behalf of a third person) sealed in a clay envelope to be delivered to that person with terrible threats if opened beforehand.

Although in most cases the questions and oracle’s answers are very straight forward, we learn (especially from Herodotus in The Histories) that more difficult and complicated questions, like those asked by the fabulously wealthy ruler Croesus of Lydia, may have been met with ambiguous answers capable of being interpreted in a number of ways.

Red-figure vase showing Pythia on tripod and priest

THE OFFERINGS

As Herodotus tells us, Croesus seems to have been particularly unfortunate as regards receiving ambiguous answers from the Oracle. Despite this, as Herodotus tells us, he continued to offer opulent gifts to her as well as attempting to ‘win her over with a magnificent sacrifice…in which he burnt in a huge pile a number of precious objects’.

Gold and ivory head of Apollo and of Artemis

Whether the magnificent burnt gold and ivory (chryselephantine) heads of Apollo and Artemis, along with hammered gold fragments of their drapery, found close to the temple are part of Croesus’ sacrifice is not clear but they certainly bear witness to how seriously the enquirers of the Oracle took her pronouncements. It is worth noting that the oracular pronouncements of the Oracle can now be found on Wikipedia.

Whilst nearly all the thousands of statues that we are told by Pliny and others embellished the sanctuary have been plundered or destroyed, a small number survive, mainly because they were buried by landslides after Delphi had been closed down by the Byzantine emperors in early Christian times. These are now exhibited in the nearby Delphi Museum and include the monumental limestone statues of Kleobis and Biton, sons of the priestess of Hera, who died peacefully in their sleep as a reward by the gods for transporting their mother during the height of summer from Argos to the Sanctuary of Hera.

We also have the finest rendition of Antinous, favourite of the emperor Hadrian, who (in rather mysterious circumstances) drowned in the River Nile. The grieving Hadrian ordered that cities throughout the Roman empire should commemorate the death of Antinous by erecting his statue. As well, there is the often overlooked, but to my mind beautifully rendered, ‘Melancholy Roman’ (possibly the Roman general Titus Quinctius Flaminius) of the 2nd century BCE.

And, of course, there is the famous bronze Charioteer, dedicated by the tyrant of Gela after his chariot victory in the Pythian games c. 475 BCE. The skilful modelling of the Charioteer, especially of his face, is a very fine demonstration of the advantage of working in bronze.

The Charioteer

THE DECLINE

By Hellenistic times (323–31 BCE) the Oracle had begun to lose its influence, although the construction of several stoas (porches) just outside the boundary of the sanctuary was financed by Hellenistic rulers, such as those from Pergamon in Asia Minor. During Roman rule, while the Oracle was still consulted from time to time, Delphi served more as a place to visit out of curiosity and as a source of plunder of its valuables by warring generals. In this regard the emperor Nero was refused permission to consult the Oracle on the grounds that he had murdered his mother. He took revenge on Delphi, however, by removing some 500 of the bronze statues from within the sanctuary. Even after this despoilation, Pliny tells us (undoubtedly an exaggeration) that there were over 3000 statues still remaining!

Following the arrival of Christianity in the 4th century CE, the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I closed the sanctuary down. An attempted revival of the Delphic Oracle by the non-Christian Byzantine emperor Julian (332–363 CE) was met by the following response:

“Tell the Emperor that the place blessed by art lies in ruins, that Phoebus Apollo no longer has a home and a prophetic laurel; no longer does the spring serve him; the murmuring water is hushed.”

And so Delphi lay buried under the debris of later landslides and the small village of Kastri until the French and Greeks commenced excavations in 1892, allowing us to envisage and ponder the splendour and importance of Delphi’s past.

French-Greek excavations uncover the statue of Antinous

Tour Greece

Agamemnon To Alexander

You can explore this extraordinary site on our upcoming tour of Greece in April 2026.

This 19-day tour, led by archaeologist Dr John Tidmarsh, takes us from the palaces of Crete and the temples of Athens to the sacred sanctuary of Delphi, the monasteries of Meteora, and the legacy of Alexander the Great in Macedon — bringing to life the myths, legends and rulers who shaped the ancient world.