Sezincote House

A Mughal Palace in the Cotswolds

The Cotswolds have been much in the news lately. Not only do the King (at Highgrove), the Beckhams, the Camerons, Kate Moss, Hugh Grant, various minor royalty, and of course Jeremy Clarkson at Diddly Squat have homes there, but now it’s wealthy Americans who have made the Cotswolds their summer holiday destination of choice.

Just last month, vice-president JD Vance arrived in this bucolic paradise for ‘a quiet break’ with his family plus the obligatory 21-vehicle security detail. Peaceful it was not!

Peter Schrank, The Times, 13 August 2025

With rolling hills, patch-work fields, honey-coloured stone villages and centuries-old manor houses with their ancient walled gardens, the Cotswolds encapsulate the quintessential beauty of rural England. Stretching across six counties of the centre and south-west of the country – from Oxford in the east to Bath and Gloucester in the west – they form the backbone of what was once the ancient Kingdom of Wessex.

It's a landscape full of surprises at every turn and some superlative gardens, both public and private. But even in this landscape of surprises, nothing quite prepares you for your first view of Sezincote House in Gloucestershire. The poet John Betjeman was a frequent guest when a young student at Oxford in the 1930s and captured the experience in his long, autobiographical poem Summoned by Bells:

Oxford May mornings! When the prunus bloomed

We’d drive to Sunday lunch at Sezincote:

First steps in learning how to be a guest,

First wood-smoke scented luxury of life

In the large ambience of a country house.

Heavy with hawthorn scent were Cotswold lanes,

Golden the church towers standing in the sun.Down the drive,

Under the early yellow leaves of oaks.

The bridge, the waterfall, the Temple Pool -

And there they burst on us, the onion domes,

Chajjahs and chattris made of amber stone:

‘Home of the Oaks,’ exotic Sezincote!

Stately and strange it stood, the Nabob’s house,

Indian without and coolest Greek within.

Sezincote in the 1930s at the time Betjeman was a frequent guest

Sezincote – etymologically Cheisnecote – means ‘the place of the oaks’ from the French chêne, oak and cote, dwelling. At the end of the 18th century, the original house was a dark and damp, run-down Jacobean manor. The story of its metamorphosis from an ugly grub into a glorious butterfly – the extraordinary building you see today – begins with three brothers, John, Samuel and Charles Cockerell, descendants of the diarist Samuel Pepys (their grandfather had been the nephew and heir of the great diarist).

In 1796, the eldest brother Colonel John Cockerell, a career soldier with the East India Company, returned to England after a glittering career but with a very modest fortune. He was said within the family to be ‘hopeless with money’ unlike his younger brother, Charles, a fabulously wealthy banker and later MP who had made his fortune in Bengal as an administrator with the same East India Company. Mindful of the need to live in a style befitting his position, and also to be near his friend and mentor at Daylesford, the creator of the British Empire in India Warren Hastings, John bought the run-down manor at Sezincote. It was all he could afford. Two years later he was dead.

The estate passed subsequently to Charles, who in turn commissioned his brother Samuel, a successful London architect, to design and build an Indian house in the Mughal style of Rajasthan, complete with minarets, peacock-tail windows, jali-work railings and pavilions. (The Mughals were an Islamic, Persian-speaking dynasty whose influence and power in India were eventually curtailed by the British East India Company). The design team included the artist Thomas Daniell, an Indian specialist, to advise on detail and the landscape designer Humphry Repton. Charles’s town house was 147 Piccadilly, next door to the Duke of Wellington.

There’s a wonderful painting by Daniell of the Prince Regent visiting Sezincote in 1812. The Prince is in the yellow coach approaching the bridge on the bend in the drive, and the picture today hangs in the entrance hall to the house.

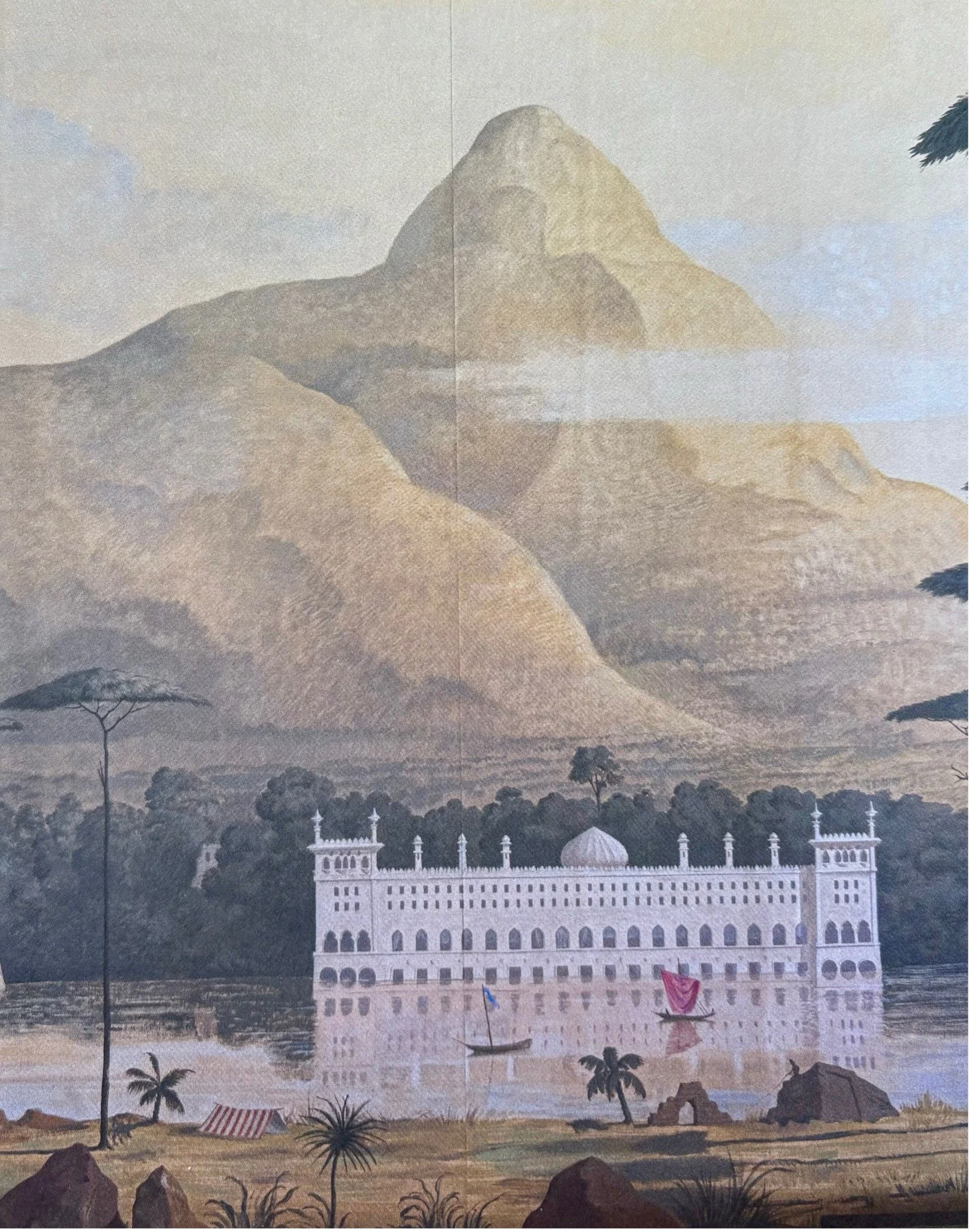

Thomas Daniell, Sezincote from the North, 1816

It was this visit that gave the Prince the inspiration to create something similar in Brighton. Initially it was Repton who offered a design modelled on Sezincote, but on a far grander scale. He was to be disappointed though as the commission went to the leading Regency architect John Nash who built the Pavilion in Mughal style – the Brighton Pavilion that we know and love today.

Samuel Cockerell designed Palladian mansions in the style of the day, and it is indeed said that Sezincote is a Palladian mansion inside a Mughal shell. Inside all is Greek Revival perfection, the fact of which makes the house unique. One might imagine that this mix of cultures would strike a somewhat discordant note but rather the pure lines of both work in complete harmony. The transition as you enter the house is exquisite.

Following its completion in 1813, attention then turned to the grounds. It was here that Daniell used his years of experience in India to create something remarkable and exotic that survives as is today. At the top of the garden is a temple to the Vedic sun god, Surya. Below her is a female yoni-shaped Temple Pool into which the waters from the local spring empty via a male lingham-shaped fountain.

The spring waters in turn descend through the grounds to a lake at the bottom and so eventually into the River Thames. Seven pools along its length offered fashionably Picturesque views of the gardens and surrounding countryside. At the half-way point, Daniell built his extraordinarily elegant Indian Bridge to take the sweeping drive up to the house (it can be seen in the painting of the Prince Regent’s arrival above).

Seen from below (as left), the underside of the bridge has the appearance of a Hindu pavilion of pleasure; inside the forest of columns are stepping stones and a Philosopher’s Seat on which the visitor can sit and contemplate the play of reflected light. At the summer solstice the last rays of the setting-sun shine directly above the top of the Temple to Surya and onto the Seat. The three-headed snake winding up a tree trunk on the small island symbolises spiritual wisdom, compassion, and power.

On top of the bridge, Brahmin bulls face each other. Cockerell insisted on this arrangement the better to frame the view, while Daniell had wanted single central bulls looking up towards the house as a symbol of divine protection. ‘Could Viswakarama, The Artist of the Gods of the Hindoos, take a peep at Sezincote, he would say let the bulls remain where they are’, wrote Cockerell to Daniell.

Following Charles Cockerell’s death in 1837, the house fell into decline at the hands of his successors who were eventually bankrupted by the Agricultural Depression of the 1880s. The family was evicted and Sezincote placed on the market. Its Indian background no longer a selling point, it took five years before a buyer was found – James Dugdale, a Lancashire industrialist who was succeeded by his son, the charming Colonel Arthur Dugdale.

The Dugdale Years from 1884-1943 were a time of family, friends and great happiness. The architectural historian, James Lees-Milne, another young visitor in the 1930s, remembers Dugdale and ‘his enchanting, beautiful and idiosyncratic wife, Ethel [otherwise known as Outoo].’ ‘In that decade’, he continues, ‘Sezincote was very different from the spruce place it is today. It resembled an Irish country house, a trifle down at heel, a little chaotic, very dog-ridden, but cosy.’

Dugdale died in 1941, not before the dome of the house had been camouflaged to prevent German bombers using it as a guide point on their route to Birmingham. His son John, an aspiring Labour politician felt the house unsuitable for his intended career and in 1943 once again it was on the market.

Here things could have gone horribly wrong. There had never been quite enough money for essential maintenance; there were memories of ‘buckets under leaky roofs and mustard-brown paint to cover neglected woodwork’. The dome was becoming unstable and there was rumour of a demolition order on the house itself. Money was needed, a lot of it, and in 1944 it came in the person of the new owner, Sir Cyril Kleinwort and his wife Elizabeth. Kleinwort was chairman of Kleinwort’s private bank in London, later Kleinwort Benson. No expense was spared in the complete restoration of the house and its interiors into their principal residence. Elizabeth, or Betty as she preferred, oversaw the interior renovation working with a young John Fowler, later of Colefax & Fowler fame to recreate the house’s original Regency ethos and splendour.

When first built, Sezincote was pure white – white stone with white domes (have a look again at Daniell’s picture, above, of the Prince Regent’s arrival). Over time the stone mellowed to a rich honey colour and, as mentioned, the dome was camouflaged in the 1940s. On removal of the camouflage, Kleinwort decided that the verdigrised copper was more in keeping with the colour of the stone than reverting to the original white, giving us the building we see today.

In 1975, Cyril and Betty left Sezincote to their youngest daughter Susanna and her husband David Peake, Cyril’s successor as chairman of Kleinwort Benson. Their parting gift was to have the walls of the dining room covered, floor to ceiling, with the most simply exquisite murals of the Indian landscape complete with examples of buildings that were the original inspiration for Sezincote nearly 200 years earlier. To see these murals in situ is worth the visit alone. They’re the last thing you see on a private tour of the house before stepping out again into this most extraordinary of landscapes.

Sezincote Dining Room Mural (detail), George Oakes, 1982. From the endpapers to Edward Peake, Sezincote, A Brief History 2024

David and Susanna in turn moved on in 2004 leaving the house and gardens to the care of their son Edward and his wife Camilla. The garden now thrives under the care of head gardener Greg Power who, together with Edward, will be welcoming us to Sezincote next year as just one of the highlights of our new From Bath to Cheltenham: The Great Gardens of Wessex tour.

Incidentally, for those who like to get these things right ‘Sezincote’ is pronounced ‘Seas-in-coat’. I’m thankful too to Edward Peake for family insights from his delightful new book, Sezincote: A Brief History, 2024 and also for his help in planning our visit next year.

GREAT GARDENS OF WESSEX

FROM BATH TO THE COTSWOLDS

From sweeping Capability Brown parklands to intricate Arts and Crafts–style designs, this new 11-day tour, led by garden historian Mike Turner, explores this region's rich variety of gardens at the height of the English spring, when tulips, wisteria and early roses are at their best.