Gertrude Jekyll & Sir Edwin Lutyens

a collaboration of genius

A special highlight for me personally in putting together our new tour Great Gardens of Britain: A Journey through Landscape has been the chance to revisit two of my great heroes, two of the most influential figures of the Arts & Crafts Movement, the garden designer Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932) and her close friend and collaborator, the architect Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944).

The more so with the publication next year of a new book Sir Edwin Lutyens: Britain’s Greatest Architect? written by my friend, former Country Life editor Clive Aslett. Those of you have travelled with us before might remember visits to Castle Drogo, Lindisfarne, Hestercombe, Barrington Court and Great Dixter, all of which have been touched by the genius of either one or both of them.

The new tour will now finish with a final-day visit to two not-before-visited houses designed by Lutyens with gardens laid out by Jekyll – Goddards and Munstead Wood, Jekyll’s own home for the last 40 years of her life.

Munstead Wood, Surrey. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens for Gertrude Jekyll

Gertrude Jekyll was born in London in 1843, the fifth of seven children of Edward and Julia Jekyll, the daughter of the banker Charles Hammersley. An interesting piece of trivia is that her brother Herbert was a friend of Robert Louis Stevenson who commemorated their friendship by using the family surname for the title of his famous book, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

When Jekyll was aged five, the family moved to Surrey where she developed a life-long love for the heaths and woods of the unspoiled countryside and its abundant wildflowers, as well as for the distinctive hand-crafted, timber-framed, tile-hung vernacular of the local villages.

Among his many accomplishments, her father Edward was a connoisseur of Etruscan pottery and so a good friend of Sir Charles Newton, Keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum.

Ralph Caldecott. 'Ceremony of Removing a Piece of Sculpture in the British Museum'. The bearded figire is Sir Charles Newton

Newton’s wife Mary was a friend of John Ruskin and it was with the Newtons that Gertrude made a ‘Grand Tour’ of Greece and the islands aged 20, discovering a passion for collecting native plants which, as on subsequent overseas trips, she sent home.

Influenced by her many Arts & Crafts and Pre-Raphaelite friends and acquaintances, Jekyll became a highly accomplished craftswoman, artist, plantswoman and interior designer. She also now moved in the circle of William Robinson of Gravetye Manor, publisher of the influential magazine The Garden - to which Jekyll contributed - and champion of ‘wild gardening’, a direct Arts & Crafts response to the formalism of Victorian carpet bedding. Our final night dinner on tour will be at Gravetye, with its glorious garden and now Michelin-starred restaurant.

Looking in and out on to the garden at Gravetye Manor, venue for next year’s tour’s final night dinner

Failing eyesight in her 40s meant that Jekyll had to take her craft and painterly skills exclusively to a broader canvas – the garden. She was later to describe the creation of a new garden as ‘doing living pictures with land and trees and flowers’.

The scale of her achievements and of her transformative influence on gardening around the world can be seen in the fact that she created over 400 gardens in the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States and wrote over 1000 articles for magazines such as Country Life and The Garden.

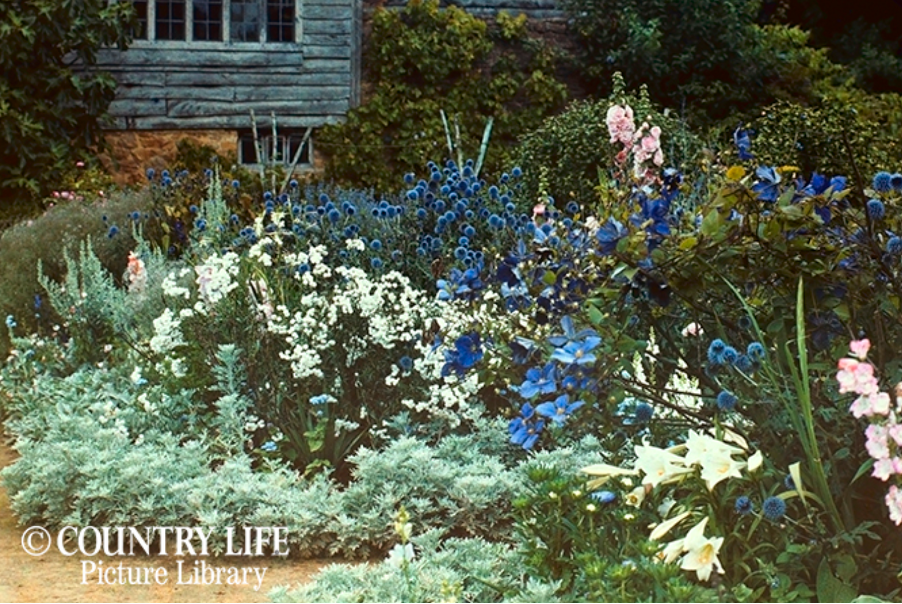

The grey border and loft. Gertrude Jekyll's garden at Munstead Wood - photographed in 1912 © Country Life Picture Library. The grey border was to be the inspiration for Vita Sackville-West’s White Garden at Sissinghurst which we will also be visiting

One summer’s afternoon in 1889 at a garden tea party, Jekyll met the much younger, by some 26 years, painfully shy yet precocious, 19-year-old Edwin Lutyens, known universally as Ned. (Edwin Landseer Lutyens was named after his father’s friend, the artist Sir Edwin Landseer.)

She was looking for an architect to design her new house and he was just breaking into the world of country-house design. Although they hardly exchanged a word, she was intrigued by his equally passionate love of local Surrey craftsmanship and vernacular, and on leaving asked him to call on her the next day. And in such a simple, happenstance way began an extraordinary collaboration of over 120 joint-commissions.

Lutyens’ future wife, Lady Emily Lytton, on first meeting Jekyll described her as ‘the most enchanting person and lives in the most fascinating cottage you ever saw. Mr Lutyens calls her Bumps, and it is a very good name. She is very fat and stumpy, dresses rather like a man, little tiny eyes, very nearly blind and big spectacles. She is simply fascinating.’ (D. Pollen, I Remember, I Remember. Privately published 2008. As quoted by Clive Aslett)

Miss Jekyll ‘Bumps’ as drawn by Sir Edwin Lutyens, c. 1896

Jekyll and Lutyens scoured the local countryside in a dog cart looking for inspiration for Munstead Wood, a house that was to cement Lutyens’s reputation. In 1910, Lutyens was asked to design a house and garden at Dixter in East Sussex for the architectural historian Nathaniel Lloyd. On to an existing 15th century manor house, Lutyens ingeniously added a similar manor house transported wholesale from Benenden in Kent, some 15k away. Lloyd, his wife Daisy - a friend of Gertrude Jekyll - and Lutyens then designed a Jekyll-inspired Arts & Crafts garden.

It typically included a rose garden, ‘the Lutyens Rose Garden’. In 1993, Nathaniel’s son, the famous garden writer Christopher Lloyd (1921-2006), who had met Jekyll as a boy and been mesmerised by her, together with his head gardener Fergus Garrett, controversially decided to remove the roses and turn the area into what was to become their influential Exotics Garden.

Great Dixter. The Long Border

Eyebrows were raised. Letters to the papers were written. Removing the roses proved ‘a wicked pleasure’ for Lloyd, ‘the noise of tearing old rose roots as they were being exhumed was music to my ears … it reminded me of a hyena devouring a plank of wood’!

Garden-wise we come full circle. Robinson inspiring Jekyll. Jekyll inspiring Christopher Lloyd. Lloyd inspiring Garrett. Garrett inspiring his former assistant at Dixter Tom Coward, who is now head gardener at Robinson’s Gravetye.

Following Jekyll’s death in 1932, the Munstead Wood estate was sold off piecemeal, the house itself in 1948. Subsequent owners have sought to both reunite the estate and to maintain Jekyll’s aesthetic both in the house and in the garden. In 2023, the property was gifted to the National Trust.

Sir Edwin Lutyens. 1921. Wikiwand

From major country-house design (over three dozen) to some of the most iconic British buildings and war memorials, his works also included the Cenotaph in London and the Thiepval Arch on the Somme; Castle Drogo and Lindisfarne Castle; the fountain in Trafalgar Square; the imperial viceroy’s palace in New Delhi, its footprint bigger than Versailles; the unbuilt Catholic Cathedral in Liverpool which would have had a larger footprint than St Peter’s in Rome and a bigger dome (only the crypt was built before war broke out after which tastes changed); and a personal favourite, the delightful British School at Rome.

Despite this, after the Second World War, Lutyens became a much-vilified victim of Modernism. Only in the last 30 or so years has his reputation been restored to the degree that Clive Aslett’s new book can indeed ask the question: Is he Britain’s greatest ever architect?

Castle Drogo, situated high above the Teign Gorge, was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens for self-made millionaire Julius Drewe

GREAT GARDENS OF BRITAIN

A JOURNEY THROUGH LANDSCAPE

From landscapes of the early 18th century through to those of the present day, this new 14-day tour led by Mike Turner visits 18 of the most beautiful and exciting garden landscapes in Britain.