José Martí – Cuba’s Hero

2023 is the 170th anniversary of the Cuban independence hero José Martí’s birth. Cuban specialist and Chairman of the International Institute for the Study of Cuba, Dr Stephen Wilkinson, explains why Martí is so important…

“I come from all places and to all places go”

José Martí

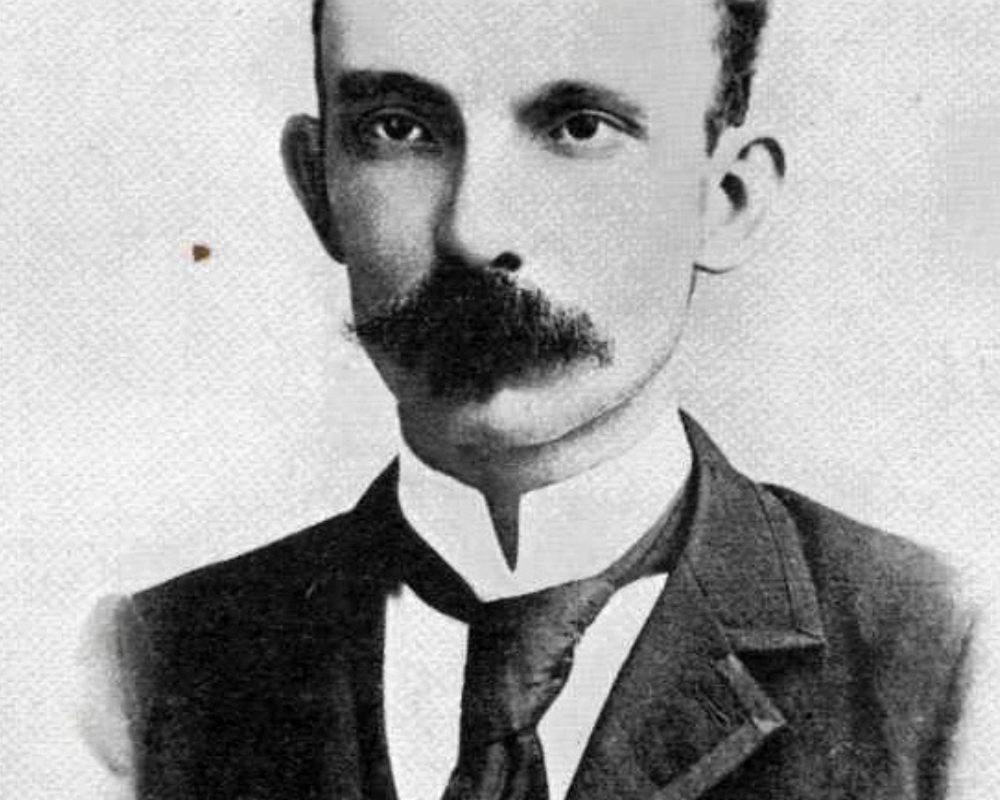

Every visitor to Cuba who lands in Havana arrives at José Martí International Airport. If the visitor is observant, as they walk through the streets, they will notice that outside the entrance to every school stands a bust of a moustachioed slightly balding man. That, too, is José Martí, and when the visitor takes the tour to Revolution Square, where all the great rallies are held, they will see that it is presided over by a giant statue of this man whom Cubans call their ‘apostle’.

If the traveller is lucky enough to scale the country’s highest mountain, el Pico Turquino, they will find a bust of Martí at the peak. So who was Martí and why is he so important?

Primarily, Martí is remembered as the architect of the last Cuban War of Independence against Spain, and as a martyr in that struggle, for he died in the early months of fighting in 1895 at the age of just 42. In such a short life, Martí accomplished astonishing things. The possessor of a truly exceptional intellect, he was a writer and activist, philosopher and a considerable poet, regarded as one of the greatest modernist poets in the Spanish language.

Marble statue of Jose Marti in HavanaImmensely popular, the words of his autobiographical poem, Los versos sencillos (the simple verses), provide the lyrics to the anthem Guantanamera. He was also a journalist, orator and polemicist, an advocate for women’s and black rights and for children. Martí’s collected works run to 25 volumes. He was the inspiration for generations of revolutionaries struggling for Cuban independence and, more than Marx, the prime motivator for Fidel Castro and his followers in their rebellion against the corrupt and venal rule of the dictator Fulgencio Batista.

Indeed, Castro’s initial attempt against Batista in Santiago de Cuba on the 26th July 1953, took place precisely in the centenary year of Marti’s birth. The group led by Castro called themselves ‘the centenary generation’, and their manifesto, written by Castro, made reference to Martí and the shame he would have felt on seeing what Cuba had become under Batista’s rule. After the attack, when he was tried, Castro invoked the hero in his famous defence speech, ‘History will Absolve Me’, where he quoted Martí at length.

There is no doubt that Cuba’s unique 20th-century revolutionary process owes itself to the thoughts and ideas of this 19th-century man who spent more of his life in exile outside the island than he did within it. Indeed, without his example and legacy, the revolution arguably would not have survived the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Ironically enough for a Cuban patriot, Martí came from a loyal Spanish family. His father was an army sergeant and part of Martí’s childhood was actually spent in Spain. Later, his father became a policeman in Havana.

Rather than his father, Martí learned most from his school teacher, Rafael María Mendive, who was a poet and supporter of Cuban independence. Martí was at school and under Mendive’s influence when the first Cuban war of independence broke out in 1868. The young Martí, aged 16, started his first newspaper, Patria Libre, and published poems in support of the rebels.

Tragedy ensued. Mendive was exiled to Spain and Martí was arrested for sedition. He was sentenced to six years hard labour and sent to break stones in a quarry. The sores he contracted from the shackles around his ankles affected him for the rest of his life. Thankfully, his father was able to use his influence to get his son released and sent to exile in Spain on the condition he did not return to the island. So, at the age of 18, Martí arrived in the heady atmosphere of revolutionary Madrid.

José Martí - Portrait made in Madrid 1871There he studied law and later transferred to Zaragoza, where he graduated in 1874. In Spain, he became an adherent of the philosophy of Karl Christian Krause, which was popular among the Spanish avante garde at the time. Much of Martí’s own thought owes itself to this humanistic philosophy that seeks to place humankind in harmony with nature. Four years later In 1878, when Spain pardoned those who had fought in the war, he returned to Havana where he met his long-time collaborator, the black writer Juan Gualberto Gómez, with whom he would work closely in the organisation of a new revolutionary party. Martí’s stay didn’t last long. Within a year, the Spanish arrested him again and sentenced him to hard labour in North Africa. But he escaped and managed to flee to New York City, where he arrived in 1880. He was 27.

Martí resided in New York for almost 15 years and lived by his writing. He came to know the United States well, serving as the foreign correspondent for a variety of South American newspapers. He wrote movingly about the plight of immigrants, blacks, Native Americans and workers and was horrified by the racial violence he witnessed at a lynching. He was also shocked by the disdain with which people in the United States regarded those from the South.

José Martí - Portrait with his son José Francisco New York 1880In exile, Martí worked tirelessly to organise a new Cuban independence party and prepare for another attempt at rebellion. But as well as preparing for war, he also spent much time contemplating on the kind of place a free Cuba would be after victory was achieved. Unlike the United States, which he found hard and unjust, he wanted a Cuba, as he said, that would be “for all and the good of all.”

This implied a profound commitment to racial harmony. Taking the lesson from the 1868-78 war, in which black and white Cubans fought together, Martí articulated a notion of Cubanness or Cubanidad, that transcended racial difference. Martí realised, too, that the independence of Cuba would have to take place in the face of US imperialism. As a beacon of racial justice, the new Cuban republic would be an example to the world that would be in stark contrast to the United States and therefore a revolution for the whole of humankind - “My country is humanity” he wrote.

This sentiment is captured most poetically in Martí’s last, unfinished, letter that was found in his belongings after his death in battle in 1895. Of all the many thousands of citations from his works that can be found adorning walls in Cuba, this passage is the one that is etched deepest in the minds of all Cubans:

Every day now I am in danger of giving my life for my country and my duty… to prevent, by the timely independence of Cuba, the United States from extending itself across the Antilles and falling with greater weight upon the lands of our America… I have lived inside the monster. I know its entrails and my sling is that of David.

More than any other legacy, Martí’s prophesy about the United States and his biblical metaphor of Cuba being David against the Goliath of the North is perhaps the defining image that guarantees the resistance of Cubans today.

Visit Cuba in 2024

Immerse yourself in Cuba’s rich culture and vintage charm, forged through its colonial and revolutionary history, on this 12-day itinerary led by Cuban specialist Dr Stephen Wilkinson.

Experience the colourful colonial architecture and 1950’s Americana of Havana and Trinidad, with day trips to the revolutionary town of Santa Clara, the unique ecovillage of Las Terrazas, and the historically significant Bay of Pigs.