Runic writing in Medieval Bergen

As it turns out, it’s not too difficult to set yourself up as an expert in runic inscriptions, particularly if you’re concentrating on the raised runestones of the Viking Age.

Nearly all of the thousands of Viking-Age memorial stones erected all over Sweden, and to a lesser extent Denmark and Norway and their overseas territories, comprise a variant of a simple formula naming the commemorator who raised or commissioned the stone monument in memory of the deceased. The stereotypical formulation generally runs as follows: X raised this stone/memorial in memory of Y, his father/son. The only tricky task is deciphering the names, but this can generally be blamed on the state of the stone or the (somewhat unsatisfactory) nature of runic writing whereby one rune represented a variety of different sounds – it’s up to the reader to work out which.

There are some variations on this formulation - a number of Viking runestones were in fact raised in memory of, or even by women - and some stones provide interesting further information such as a prayer, a laudatory epithet (‘generous with food’, ‘the best of yeomen’, ‘wise in words’) or details of who carved it, with a number of professional carvers even known by name. You may even find out where or how the person died! From neighbouring Finland to far-flung Greece or Constantinople: around 30 runestones mention an expedition with Ingvar the Far-travelled to the land of the Saracens, and several commemorate taking ‘danegeld’ in the Viking raids in England. We encounter rare sentimentality in Swedish Södermanland: ‘No one will bear a better son’; and gnomic wisdom in the Isle of Man: ‘Better to leave a good foster-son than a wretched son’; while the Danish mother Thyrve raised a runestone ‘in memory of Thorbjorn, son of Sibba, her cousin, towards whom she felt more kindly than towards a son of her own’. But these are few and far between. Look at a lump of runic stone in Sweden and it’s usually not too hard to guess what information you’ll find there.

Although disappointingly laconic, many of these Viking Age stones are elaborately decorated, sometimes illustrating familiar scenes from Germanic mythology. This wasn’t the case from the beginning. Runic writing began to appear in the Scandinavian countries in the first centuries of the Common Era. Many of the earliest inscriptions are short and often bafflingly enigmatic (most commonly names or magic formulae, scratched into weapons, jewellery and other early artefacts), and it’s only later that they develop into the commemorative lapidary formulations so typical of the Viking Ages.

Traditional Rune stone found in a Swedish forest, carved in 11th century.

The situation is very different when it comes to the later runes, though – something that really wasn’t appreciated until half of the medieval wharf area of Bergen, the old economic centre of Norway, went up in flames in 1955. The loss of several beautiful old wooden buildings dating from the 11th and 12th century was devastating, but from amidst the horrendous wreckage of this beautiful Norwegian town emerged hundreds of runic sticks – seemingly rubbishy, inconsequential scribbles of runic writing on scrappy bits of wood. But what writing! It is because of these sticks, unearthed during the 13 years of subsequent excavations that we have a wealth of mediaeval runic texts and know that, far from being restricted to the ceremonial funeral script of the privileged few, runes were commonly employed as everyday writing in medieval Bergen – and likely in many more towns throughout Scandinavia.

The Bryggens Museum houses thousands of artifacts and modern historical and archaeological research to let you come closer to the everyday lives of the medieval people of Bergen and Western Norway.

The runic texts, many of which are on display in the Bryggens Museum (Bergen City Museum), bring to life a world full of trading, drinking, prayers, enchantments and (very often) sex that would otherwise have remained undiscovered. ‘Gyda says that you have to go home’ is written on one side of a runic stick (I like to imagine it was found in the ruins of a tavern) with indecipherable scrawl (was some errant husband trying to respond?) scratched on the other side. Maybe it was in that same tavern that someone carved ‘Now there is a great fight’. Another makes a simple wish: ‘If I might only come much more often in the vicinity of the mead-house’. There are declarations of love and desire: ‘My love, kiss me’, ‘Think of me, I think of you. Love me, I love you’, ‘If you love me, I love you, Gunhild. Kiss me, I know you well’ or, more poetically, ‘I was blessed when we sat together and no one came between us’, to even burning passion: ‘I so love another man’s wife that fire seems cold to me’. Sometimes the sentiment seems somewhat narcissistic: ‘I can say to you, as you will experience with me, that I will love you no less than myself’, or even downright nasty: ‘Evil has the man who has such a woman’. There are crude boasts of sexual conquest, of which the least offensive reads: ‘Ingeborg loved me when I was in Stavanger’. But of course it’s not all hearts and genitalia. There are requests for provisions: ‘Tore Ovhard owns the salt … And you can count on the payment to my knowledge’, and delivery statements: ‘Thorkel Moneyer sends you pepper’, to hundreds of statements of ownership and runic requests from high-ranking officials: ‘Sigurd Lavard sends God's and his greetings ... I would like to have your forgings for arms...’, along with advice: ‘Cut a letter in runes to Olaf Hettusvein's sister. She is in the convent in Bergen. Ask her and your kin for advice when you want to come to terms. You, surely, are less stubborn than the Earl…’.

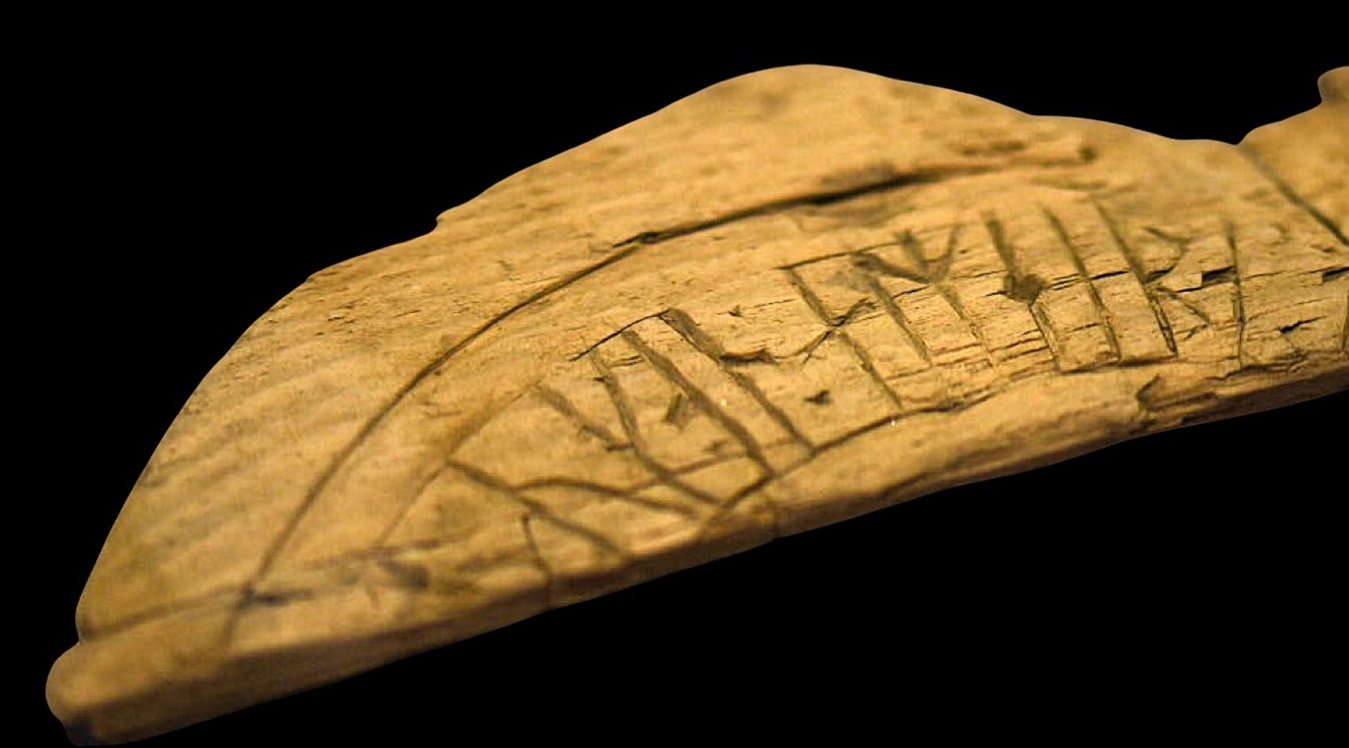

Romantic runic inscription and control notches: “Please love me” on one side and notches on the other, probably showing the number of sacks or barrels that were unloaded or loaded on merchant ships. The wooden stick is about 11cm long.

There are verses and curses, some of which reference the old gods, or invoke elves, trolls, ogres and valkyries, promising torment and misery unless you ‘love me as yourself’: ‘I carve cure-runes, I carve help-runes, once against the elves, twice against the trolls, three times against the ogres’. Further afield, from other Norwegian towns we find proposals of marriage: ‘Havard sends Gunhild his friendship and God’s greeting. And now it is my full desire to ask you for your hand in marriage, if you do not want to be with Kolbein. Think over your intentions ... and have me told your desire’, and scathing homosexual insults – all very different from the repetitive raiser formulas from centuries earlier.

Bryggen in Bergen has been a busy part of the city since the Middle Ages. Both the oldest wooden buildings and the thick cultural layers located below ground appear on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

The point of all this is simply that it shows how unremarkable the use of runic writing in an ordinary urban environment was: runes have been called the ‘post-its’ of the Middle Ages. Of course we have no way of knowing the rate of runic literacy at that time but it seems to have been remarkably high. People used runes in all kind of contexts: from locker-room boasting to high-level diplomacy, for profane, religious and magical purposes, for requests and receipts, in poetry and prose written in Scandinavian languages as well as in Latin. One of the Bergen runic sticks probably dating from the 13th century even illustrates a fleet of nearly 50 ships, some decorated in familiar Viking dragon-head style.

Inevitably, perhaps, the use of runic writing died out as it was superseded by the use of the Roman alphabet, displacing the runesticks unearthed in Bergen and some other Scandinavian towns. But the beauty of all runic inscriptions, of course, is that even if not as off-beat or interesting as the ones discussed above, they inevitably tell you something about the context in which they are made, not just about language or orthographic development but so much more.

Few other artefacts of the Middle Ages give you such a direct link to the feelings of those who lived in the past. Even when not carved by ‘the man who is most rune-skilled west of the sea’ (the boast of a mediaeval inscription graffitied into the walls of a neolithic tomb in the Orkney islands), a simple inscription of just one or two words, or even one or two runic characters, lets 21st century readers know that someone, somewhere, thought something was worth recording hundreds of years ago – and if you allow it, it can provide you with an insight into the world in which that long-ago carver of runes lived.

ONLINE COURSE: MEDIEVAL SCANDINAVIA

Take a closer look at the medieval rune-sticks - the ‘post-it notes’ of the Middle Ages - with Dr Mindy Macleod on her online short course commencing this coming Thursday, at 6.00pm AEST. Across two sessions, Mindy examines some of the runic texts unearthed from excavations in the medieval port town of Bergen before venturing beyond the city to look at artefacts found elsewhere - on church furnishings, lead amulets, and even graffiti - to tell us about everyday life in this period.

2 x 90-minute sessions: August 18 & 25, 2022 @ 6.00pm AEST