The Utopian Dream of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Homes

Wright's Jacobs House I, widely considered to be Wright’s first Usonian structure (Photo by James Steakley)

You’d be forgiven for thinking that the renowned 20th-century American architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed only for the wealthy elite.

After all, household-name architects (or “star-chitects”) like Wright don’t typically get famous by creating homes for the average family.

Like his architectural peers, Wright did, of course, design a number of innovative public and commercial projects. These include New York’s Guggenheim Museum; the S.C. Johnson Wax Administrative Complex in Racine, Wisconsin; Tokyo’s beautiful but now-demolished Imperial Hotel. and the similarly demolished Larkin Administration Building in Buffalo, New York.

Guggenheim Museum, New York

Most know Wright, though, as the designer of lavish private residences such as Fallingwater, a vacation home in the western Pennsylvania hills designed for Pittsburgh department store owner Edgar Kaufmann; the Robie House (an iconic example of Wright’s Prairie Style); the Hollyhock House in Los Angeles, created for a wealthy oil heiress; and Wright’s own home-as-architectural-laboratory, Taliesen in Spring Green Wisconsin.

Fallingwater, Mill Run, Pennsylvania

But throughout his long career, Wright also imagined an architecture for more modest budgets. His very first houses in the Oak Park district of Chicago were mainly for middle class clients. In 1901, The Ladies Home Journal commissioned Wright to design a house that the magazine promised could be built for $5,835.

Frank Lloyd Wright's design for an inexpensive house made of concrete, originally published in Ladies Home Journal in April 1907

In his early Prairie Style period, Wright had the idea of family residential housing designs that would share style, structure and parts, similar to the Sears Roebuck Catalogue style homes, but architect designed. He partnered with a developer, Arthur L. Richards, in 1911 to offer designs that were standardised and modular, so customers could choose from 129 models on seven floorplans and three roof styles. Unfortunately, due to a falling out with his partner - a scenario that would be repeated throughout his career - there was only ever about 25 American System-Bulit homes constructed and it is thought that only 12 have survived. The largest concentration of them is in the Burnham Block in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Burnham Block – American System Built Houses

In the mid 1930’s, in the depths of the Great Depression, and just before Wright’s renaissance with both the Johnson Wax Administration Building and Fallingwater, Wright was challenged by a local newspaperman in Madison, Wisconsin, Herbert Jacobs, to build a home for the “everyman” to cost no more than $5,000. Wright designed what is now known as Jacobs House I and the cost was brought in at $5,000 plus the $500 architect’s fee.

Johnson Wax Administration Building, Racine, Wisconsin

To minimise construction cost the house featured plywood sandwich walls, a floating concrete foundation pad and bricks “borrowed” from the Johnson Wax building site. Wright also incorporated, for the first time in America, hydronic underfloor heating and a carport.

Jacobs House I, Madison, Wisconsin

He described the house as “Usonian”. This was a term that Wright used to differentiate the New World character of designing the landscape of the country, cities and buildings, free of previous Old World architectural conventions. Rather than American, it was a style unique to the United States of Northern America.

Interior of Jacobs House I, Madison, Wisconsin

Wright later said "The house of moderate cost is not only America's major architectural problem, but the problem most difficult for her major architects. As for me, I would rather solve it with satisfaction to myself and Usonia than build anything I can think of at the moment."

Visions of a Utopian America

In the pre-World War II era, Wright wasn’t alone in his penchant for dreaming up utopian settlements— in fact, Usonia had been partly inspired by Henry Ford’s never-realised “75 Mile City” project at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Intended to address some of the disconnection caused by urban life and the mechanical production of goods, Wright’s Usonian town would be built far from the city. He envisioned a regional community centered around the automobiles that at the time were not only becoming affordable, but a necessity for every American family who lived outside a major urban center.

Usonia inched its way toward becoming reality when Edgar Kaufmann (of the Fallingwater Kaufmanns) financed a detailed 12 foot by 12 foot scale model representing a hypothetical four square mile (10km2) community named “Broadacre City”. The model represented enough space for 1400 families at an acre per family and 10 acres per farmer. It was initially displayed at an Industrial Arts Exposition in the Forum at the Rockefeller Center in New York in 1935.

After the New York exposition, Kaufmann arranged to have the model displayed in Pittsburgh at an exposition titled "New Homes for Old", sponsored by the Federal Housing Administration. The exposition opened on the 11th floor of Kaufmann's Department store. Wright went on to refine the concept in later books and in articles until his death in 1959. The actual model is currently studied at the Avery Fine Arts and Architectural Library at Columbia University in New York.

Broadacre City model (photo by Skot Weidemann)

Broadacre was arranged symmetrically, with highways dividing farms and factories from residential areas. Each residential concentration consisted of a school ringed by houses, then businesses and government offices, then a variety of civic buildings, all interlaced with natural features like streams and parks. Everything was to be fully integrated. The most powerful civic authority, of course, would be a county architect, one who deeply understood the principles of organic architecture.

A “Small House with Lots of Room in It”

Wright’s Broadacre City dream never materialised — at least, not in the version he proposed. The idea’s impracticality, his refusal to work with the planning powers-that-be and the pressures of the Depression killed it. Hints of other, similar communities did emerge — the Tennessee Valley Authority’s workers’ village at Norris Village, for instance. But Wright did realise at least one part of his own Usonian vision: the houses.

The first glimmers of Wright’s Usonian houses appeared around the turn of the century, in the titles of articles he penned for the Ladies’ Home Journal: “A Home in a Prairie Town” and “A Small House with ‘Lots of Room in It.’”

Frank Lloyd Wright's A Small House with ‘Lots of Room in It.’”, Ladies’ Home Journal, July 1901

As the latter title suggests, Usonian houses were small, single-story dwellings. But Wright designed them to have a spacious feel and a connection to nature. They were built with natural, locally sourced materials. Almost every room provided access to the outdoors, and the houses were flipped so that the living area — normally the front of the house — faced the back. Cantilevered carports replaced garages.

Kinney House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1951 for Patrick Kinney (a Lancaster, Wisconsin attorney), his wife Margaret, and their three children

Wright’s Usonian houses emphasized living and community — not storage, displaying stuff or holing up away from one’s family. Usonian houses lacked attics or basements, and the whole house was designed around the living room. Light fixtures and furniture were built in. Kitchens were designed as work spaces, practically equipped for preparing food and rejoining the family.

Alvin Rosenbaum, who grew up in one of Wright’s Usonian houses in the remnants of Ford’s Muscle Shoals towns, describes the feeling of living in one of Wright’s creations:

“Growing up in a Usonian house created a series of encounters that always seemed somehow connected, as if the architecture flavored everything that flowed through it or came near it, an aroma and taste experienced by nearly every passerby, to visitors, and among our family. It is a quality to which the integration of forms and textures, the prospects from the inside looking out, the ripple of levels down a gently sloping site, the materials and the craft of their journey and finish, the extraordinary range of spaces—open and closed, dark and light, high and low, rough and smooth—all contribute”.

Rosenbaum House, Florence, Alabama

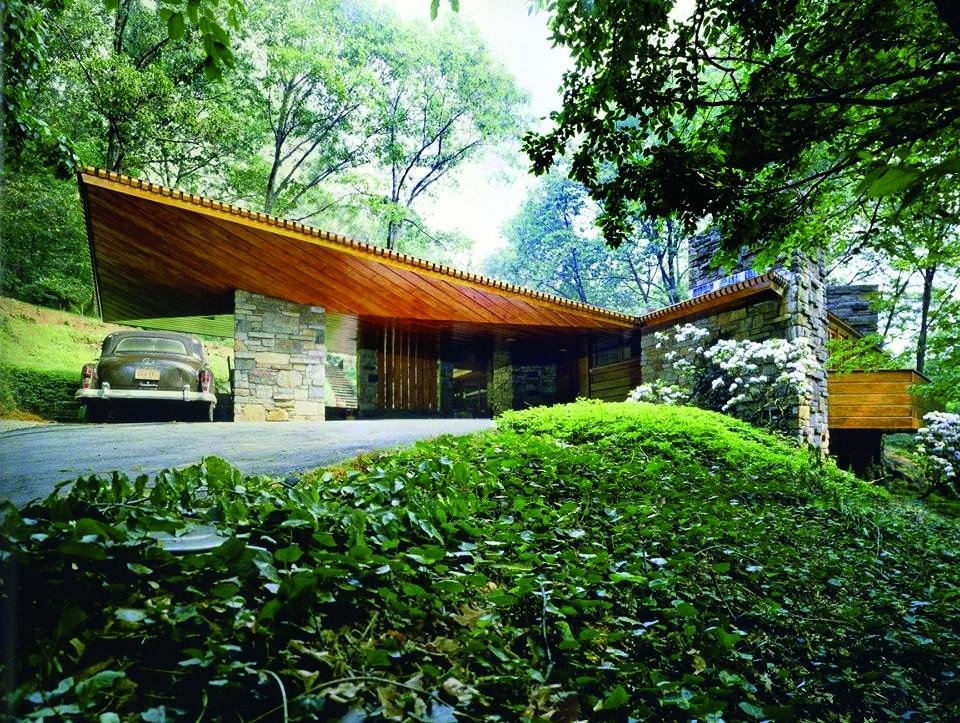

While Wright’s utopian dream remained just that, arguably his Usonian houses replicate that dream in miniature for the lucky families who get to occupy them. He brought into being a series of around 60 houses, designed with the same principles, but at a much lower cost and are now called his Usonian houses. Although his later Usonian homes, such as the Isaac and Bernadine Hagan’s Kentuck Knob in Western Pennsylvania, were not really priced for the “everyman”.

Kentuck Knob, Dunbar, Pennsylvania

His last living client, Roland Reisley, recently recalled that during the ever increasing cost of the construction of his Usonian home in the 1950’s, Wright encouraged him “Building this house is one of the best things you can do. Stop if you must, and then continue when you can,” Wright told him. “I promise you’ll thank me.”

Reisley House, Pleasantville, New York

Seven decades later, Reisley strongly agrees. He has had to make very few changes. “It has functioned for newlyweds, infants, toddlers, teenagers, and an empty-nest period,” he says. “I was a widower for a few years and have a new partner now. It worked very well for all of those stages.” Never once has he had a desire to switch things up. “That wasn’t necessary here, the house was just right.”

Interior of Reisley House, Pleasantville, New York

Not a single day has gone by that he hasn’t seen something beautiful. “The light on the stone, the grain of the wood, or something,”

Wright did create Utopia for a very fortunate few.

Roland and Ronny Reisley with Frank Lloyd Wright at the Reisley House

Tour Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses and More…

Interested in seeing Usonian houses and other classic Wright designs for yourself?

Explore the works of this great American architect on our 13-day Frank Lloyd Wright: Chicago to Fallingwater tour, scheduled for May and October 2025.

Sources

Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Design for America. The Preservation Press, 1993.

Sergeant, John. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian Houses. Whitney Library of Design, 1976.

Jacobs, Herbert. Frank Lloyd Wright: America’s Greatest Architect..Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc, 1965.

McLaughlin, Katherine. Working with Frank Lloyd Wright: The Architect’s Last Living Client Shares His Experience with the Visionary. Architecture + Design, July 2024

would love to include an image of a Usonian interior, but Shutterstock doesn't have them